Fast 5 with Stewart Nickols

Our good friend and runner, Stewart Nickols, has had a tough 12 months dealing with a very complex heart condition, that stopped him running and had him searching for answers. We asked him a few questions to find out more about what exactly is going on, how he has coped and what’s in store ahead.

1. What have you been dealing with over the past 18 months?

I’ve been suffering from electrical issues in my heart known as arrythmia’s. It started last May on a training run. I had been having odd 1-2 second sensations on runs for around 10 years – once every year or less – but in 2020 I had a couple and then on a long run in May, I had a more severe one. I went to hospital and was put on an ECG. The ECG showed that my heart wasn’t beating properly.

What happened with me was the top of my heart, the atria, gave up all rhythm and just went flibbety floppety at a crazy high rate. From May to November I bounced around a lot of specialists, until I had an operation called an ablation in November to burn out some of the bad electrical connections in my heart. The journey was made more complicated by the discovery that my heart is missing a connection. In “normal” people, the head and arms drain into a big vein called the “superior vena cava. In my heart, this blood vessel plugs into the back into the part of the heart where the heart muscle itself sends back its used blood.

Basically, everyone has the blood vessel arrangements that I have in the womb, but normally it resolves itself – so mine is called a “persistent” left SVC which really means that my heart “never grew up”. I have been running with a foetal heart.

I have two other defects. The other defect is the girth of my main vessel…. The aorta. The upper male limit for the diameter is 40mm.

My aortic root is 48mm and it grows during your life.

Anyway, back to the November operation which involved a relatively painless operation under general anaesthetic. It was called a catheter ablation and involved making a hole in my right thigh and then tunnelling up to my heart. They burnt out a loop where my heart beat appeared to trigger itself – called atrio-ventricular re-entrant tachycardia. These operations take a while to recover from and you are supposed to ignore all the pain for a few months. Two months later, I wasn’t getting any better, so in late January I went into A and E for a third time to get an ECG to prove it. While I was attached to the machine waiting for my print outs to take home, I had an episode of something called Ventricular Tachycardia.

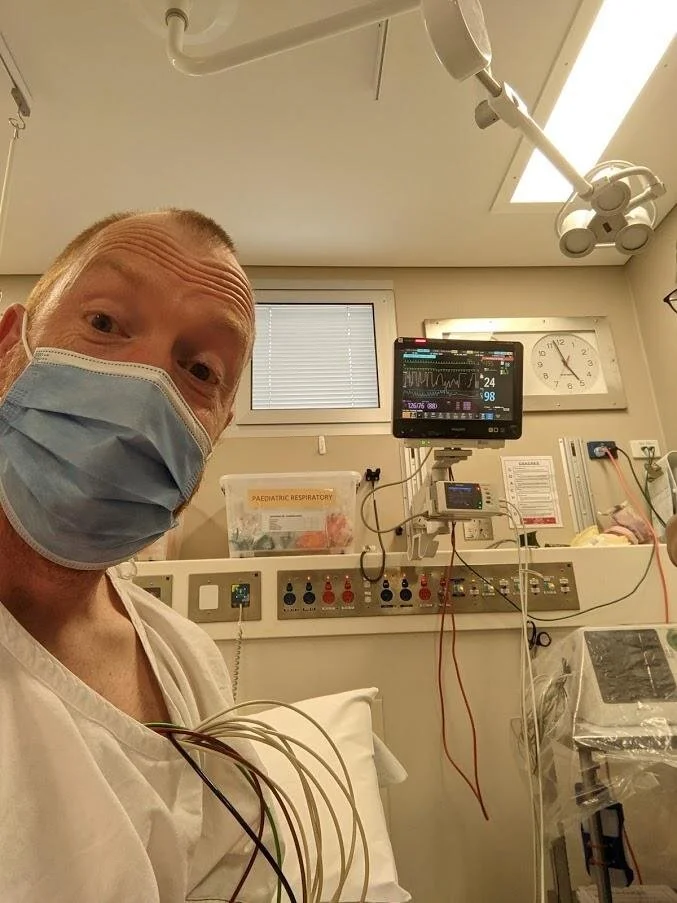

They told me that they could not release me, could not detach me from the ECG and were going to transfer me by ambulance to the Epworth into the care of my electrophysiologist. So after they tested the defibrillators next to my bed in the hospital, I was taken by two specially trained cardiac nurses in an ambulance to the Epworth. You might imagine that I felt physically bad during this medical emergency, but in fact, the arrhythmia does not always come with pain or other sensations. In the next picture, my heart rate is 195.

After a couple of nights in the hospital, I was discharged on some fairly strong drugs and told to wait for the date of my next. The date came through in the first week of February. It was 18th May. This was one of the lowest points in the whole process. After crossing off the days on the calendar like a prisoner awaiting release, and another trip to A and E with an increased prescription, it was suddenly brought forward to 20th April.

2. How has this changed your approach to life and running?

It feels to me like your heart is the second most important thing in who you are. It motivates you, powers you, and beats from your birth until your death. The only thing that scares me more is losing mental faculties. One of the tricky things was dealing with the magnitude of the decline. Going from a 90 minute half marathon to not being able to run for 30 seconds without sitting down was very confronting – like aging from a young 42 to an old 65 in a few months. And facing up to the fact that it may never be fixed.

It wasn’t just running that was affected. Here is a list of the triggers for arrhythmia

Caffeine

Excitement

Lack of sleep

Alcohol

Large meals

My life goals were things like:

Chase my six-year-old daughter through the house when she jumps out of the bath and refuses to dry herself.

Work until retirement (I don’t do physical work but it isn’t without stress)

Go to pub and have three beers and a burger without needing to go to hospital.

Be able to chase my four-year-old son around the park.

It has also changed my approach to talking to people who are very sick. People who ask me questions really want to know the answers to certain questions, but I can see that they are not asking directly – are you better? Will you get better? Are you going to die? No, maybe, and eventually.

They don’t want to know all the procedure stuff. I became aware that I did the same thing when talking to people who are very ill. When I heard procedure stuff, I just asked “what does it mean?” type questions – and the thing is that people don’t know. Doctors don’t know. They do stuff. Sometimes it works, often it doesn’t and they need to do other stuff.

Science isn’t that settled. We don’t know everything. Doctors are doing their best, but they aren’t Gods. Really we are all just left with a bunch of procedures, dates, possibilities and if we are lucky, probabilities. While it has left me much more sympathetic towards very ill people, I probably don’t have as much time for people who get down about having a sore foot – go swimming, cycling or kayaking. HTFU, it’s not like you’ve been totally robbed of the joy of physical activity.

3. What have you done to get better and cope with not being able to train in the way you are accustomed?

One important thing is to realise that your perceptions of whether you are getting better are very relative. Making notes about how you feel and the sorts of things that you can do really helps to keep your feelings objective and steady.

Garmin data and other data helps especially. I would recommend that people get familiar with their heart rates and blood pressures so that they can manage their training – especially over-training, which I suspect was a trigger for this.

If I am honest, I’m not sure that I have coped that well with this.

4. What does the running future look like for you today?

I am happy that I can wrestle with my son for five minutes without needing a lie-down and that I have hit my 10,000 steps every day for the last two weeks. This is the future that I need to be sure of. I ran 7km the other day and I didn’t need to go to hospital. I’m going to run 9km on Thursday and hopefully, I won’t need to go on Thursday either.

Beyond that, I try not to think about it and especially not publicly commit to what I hope will happen. I have too much to lose emotionally.

5. What have you learnt most about yourself since the diagnosis?

That my heart was put together by a drunken apprentice and that I can deal with more than I thought I could.